We all get frustrated when our sow/gilt return and we find that they are not in-pig (pregnant). The cause of this is not being vigilant in watching if they return (come back on heat, hogging) or it could be a case of an infection.

Causes

The main causes are poor management and infertility. With regards to management, experience shows us that empty sows and gilts are as of a result of being misidentified poorly, housed in groups running with the boar and services are not supervised and observation of post service for returns to oestrus are not detected. I know it is difficult to keep an eye on our pigs all the time, but if you know when they are due to start hogging then introducing the boar and observing can save you time and worry. Knowing if and when the sow/gilt is due to return by counting 21 days from her last hogging will help you to know if the service has been successful.

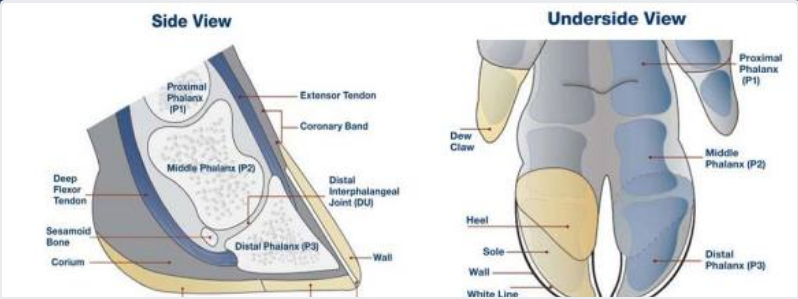

If pregnancy testing is not carried out (hire our pregnancy scanner from our website oxfordsandyblackpiggroup.org), then sows may reach term without being pregnant. Infertility may be solely responsible when observation has been a little lax. When embryos are produced and die, sows return to oestrus at uneven intervals. Where disease or cold have reduced the ability of the animal to return or where housing is such that hogging cannot be observed, then the pigs will remain undetected until a routine pregnancy check is followed or the expected farrowing date arrives with no farrowing. Sometimes, in these cases, there may be an undetected abortion, cystic ovaries or pyometra which there will be an infection of the uterine horn.

Clinical signs

‘Not-in-pig’ sows or gilts return to heat after service and also fail to develop the abdominal swelling and underline development typical of pregnancy. The sows are found to be non-pregnant when examined by. A history of vulva discharge may pinpoint the stage at which pregnancy ended.

It will come to no surprise that failure to farrow leads to a diagnosis of not-in-pig. The reasons for the failure of pregnancy can be determined by examining the records. If the recording is not carried out, services are not supervised, pregnancy checks not carried out and returns to oestrus not checked visually, then poor management is the cause.

Pigs that are in poor condition and exposed to too hot, cold, damp and drafty housing then this will result in the sow/gilt not carrying to term and possibly reabsorbing or aborting. Where records confirm that service was carried out and pregnancy has been confirmed reliably, then again, abortion or reabsorption has occurred.

Treatment and prevention

Before animals are treated as not-in-pig, a pregnancy test should be carried out, as the commonest cause of failure to return to service is pregnancy. Cystic ovaries and subdued oestrus can be treated using chorionic gonadotrophin. Pyometra may respond to antimicrobial treatment by injection and allow a return to oestrus.

Prevention is largely a matter of management, although vaccination against conditions such as parvovirus, erysipelas, leptospirosis, PRRS, and influenza can also be a reason for a non-productive sow.

Sows must be identified individually, services must be attended with good recording keeping of the boar or semen used together with results of any pregnancy tests. Ensure that mating is successful and occurs at the correct time if AI-ing that semen quality is adequate. Be vigilant to observe that there are no vulva discharges after service.

To hire our pregnancy scanner, please click here