(When sourcing stock IT IS UP TO YOU to ask the breeder if they have suffered any diseases within their herd if you don’t ask you don’t know and the breeder will and should not be offended by your question as this shows due diligence on your behalf.)

Erysipelas is caused by a bacterium called Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae in pigs and is one of the oldest recognised diseases that affect growing and adult pigs. The organism commonly resides in the tonsillar tissue. These typical healthy carriers can shed the organism in their faeces or oronasal secretions and are an important source of infection for other pigs.

Disease outbreaks may be acute or chronic, and clinically inapparent infections also occur. Acute outbreaks are characterised by sudden and unexpected deaths, febrile episodes, painful joints, and skin lesions that vary from generalized cyanosis to (a bluish discoloration of the skin due to poor circulation or inadequate oxygenation of the blood) the often-described diamond skin (rhomboid urticaria) lesions. Chronic erysipelas tends to follow acute outbreaks and is characterized by enlarged joints and lameness. A second form of chronic erysipelas is vegetative valvular endocarditis. Pigs with valvular lesions may exhibit few clinical signs; however, when exerted physically they may show signs of respiratory distress, lethargy, and cyanosis, and possibly suddenly succumb to the infection.

The genus of Erysipelothrix is subdivided into two major species: E rhusiopathiae and E tonsillarum. In addition, there are other strains that constitute one or more additional species known as E species 1, E species 2, E species 3, and E inopinata. At least 28 different serotypes of Erysipelothrix spp are recognized, and pigs are considered to be susceptible to at least 15. Field cases of swine erysipelas are predominately caused by E rhusiopathiae serotypes 1a, 1b, or 2.

On farms where the organism is endemic, pigs are exposed naturally to E rhusiopathiae when they are young. Maternal-derived antibodies provide passive immunity and suppress clinical disease. Older pigs tend to develop protective active immunity as a result of exposure to the organism, which does not necessarily lead to clinical disease. E rhusiopathiae is excreted by infected pigs in faeces and oronasal secretions, effectively contaminating the environment. When ingested, the organism can survive passage through the hostile environment of the stomach and intestines and may remain viable in the faeces for several months. Recovered pigs and chronically infected pigs may become carriers of E rhusiopathiae. Healthy pigs also may be asymptomatic (showing no symptoms) carriers. Infection is by ingestion of contaminated feed, water, or faeces and through skin abrasions.P

The acute and chronic forms of erysipelas may occur in sequence or separately. Pigs that succumb to the acute septicemic form may die suddenly without previous clinical signs. This form occurs most frequently in growing and finishing pigs. Acutely infected pigs are depressed and reluctant to stand and move. Affected pigs squeal excessively when handled, require assistance to stand, and prefer to lie down soon after being forced to stand. Affected pigs may also walk stiffly on their toes and shift weight from limb to limb when standing. Anorexia and thirst are common, and febrile pigs will often seek wet, cool areas to lie down. Skin discoloration may vary from widespread erythema (reddening of the skin) and purplish discoloration of the ears, snout, and abdomen, to diamond-shaped skin lesions almost anywhere on the body, but particularly on the lateral and dorsal regions. The lesions may occur as discrete, pink or purple areas of varying size that become raised and firm to the touch within 2–3 days of illness. They may disappear over the course of a week or progress to a more chronic type of lesion, commonly referred to as diamond skin disease. If untreated, necrosis and separation of large areas of skin can occur, and the tips of the ears and tail may become necrotic.

Clinical disease is usually sporadic and affects individuals or small groups, but sometimes larger outbreaks occur. Mortality is variable (0–100%), and death may occur up to 6 days after the first signs of illness. Acutely affected pregnant sows may abort, probably due to the fever, and lactating sows may stop producing milk.

Untreated pigs may develop the chronic form of the disease, usually characterized by chronic arthritis, vegetative valvular endocarditis, or both. Such lesions may also be seen in pigs with no previous signs of septicemia. Valvular endocarditis is most common in mature or young adult pigs and is frequently followed by death, usually from embolism or cardiac insufficiency. Chronic arthritis, the most common form of chronic infection, produces mild to severe lameness. Affected joints may be difficult to detect initially but eventually become hot and painful to the touch and later visibly enlarged. Dark purple, necrotic skin lesions that commonly separates itself from the dead tissue may be seen. Mortality in chronic cases is low, but growth rate is retarded.

Diagnosis of erysipelas is based on clinical signs, gross lesions, response to antimicrobial therapy, and demonstration of the bacterium or DNA in tissues from affected animals. Acute erysipelas can be difficult to diagnose in individual pigs showing only fever, poor appetite, and listlessness. However, in outbreaks involving several animals, the presence of skin lesions and lameness is likely to be seen in at least some cases and would support a clinical diagnosis. Rhomboid urticaria or diamond skin lesions are almost diagnostic when present; however, similar lesions can also be seen with classical swine fever virus.

A rapid, positive response to penicillin therapy in affected pigs supports a diagnosis of acute erysipelas because of the sensitivity of the organism to penicillin.

Chronic erysipelas can be difficult to definitively diagnose. Arthritis and lameness, coupled with the presence of vegetative valvular endocarditis postmortem, may support a presumptive diagnosis of chronic erysipelas.

Serologic tests cannot reliably diagnose erysipelas but can be useful to determine previous exposure or success of vaccination protocols, because antibodies should increase after vaccination.

Treatment:

As we have discussed in previous posts in the group under “Back to Basics Part IV – Handling Medications – What’s in your Cupboard ?” E rhusiopathiae is sensitive to penicillin. Ideally, affected pigs should be treated at 12-hr intervals for a minimum of 3 days, although longer durations of therapy may be necessary to resolve severe infections. On an economic basis, penicillin is the best choice for antibiotic therapy, but ampicillin and ceftiofur also yield satisfactory results in acute cases. When injecting large numbers of affected pigs is impractical, tetracyclines delivered in the feed or water may be useful. Fever associated with acute infections can be managed by administration of NSAIDs such as flunixin meglumine or by delivery of aspirin in the water. Erysipelas antiserum is described as an effective adjunct to antibiotic therapy in treating acute outbreaks but is not commonly available. Treatment of chronic infections is usually ineffective and not cost effective.

Vaccination against E rhusiopathiae is very effective in controlling disease outbreaks.

Optimal timing of vaccination may vary from farm to farm. When E rhusiopathiae is endemic in the production environment, vaccination should precede anticipated outbreaks. Susceptible pigs may be vaccinated before weaning, at weaning, or several weeks after weaning. Male and female pigs selected for addition to the breeding herd should be vaccinated with a booster 3–5 wk later. Thereafter, breeding stock should be vaccinated twice yearly. Vaccines should not be administered to animals undergoing antibiotic therapy, because antibiotics can interfere with the subsequent immune response to the vaccine.

In addition to vaccination, attention to sanitation and hygiene and elimination of pigs with clinical signs suggestive of erysipelas infection represent other viable methods that may help control the disease. But in all cases you must discuss your situation with your vets to discuss your vaccination programme.

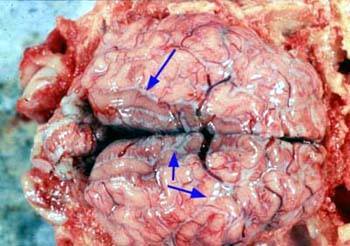

Photos courtesy of Pig333, Dr D Risco Unidad de Patologı´a Infecciosa Photo above showing findings in a lung showing good cells being suffocated by the erysipelas bacterium.