Welcome to our Pig Disease and Ailments wiki, you can search for a given term i.e “Dysentery” and it will show you all articles on that topic. This content is dynamic and updated regularly. If you have any specific content or subject you would like to see, please drop us an email .

Biosecurity serves as the pivotal strategy through which we thwart the infiltration and proliferation of Read more

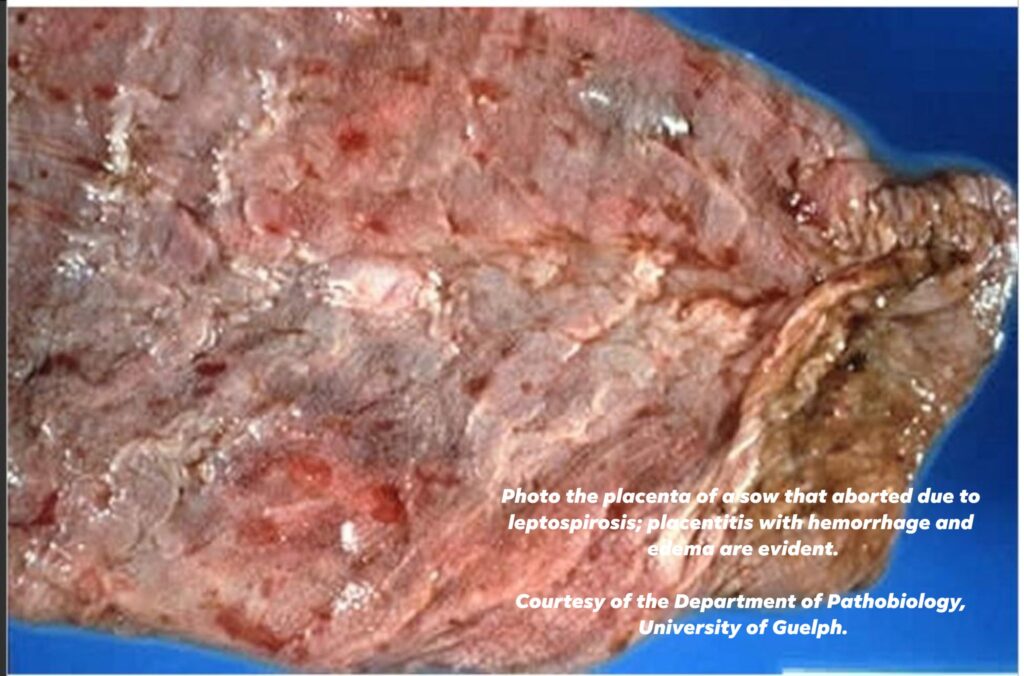

This affects all age groups from growers, gilts, sows and boars. It is caused by Read more

Understanding and Managing Cannibalism in Pigs In recent months, the Oxford Sandy and Black Pig Read more

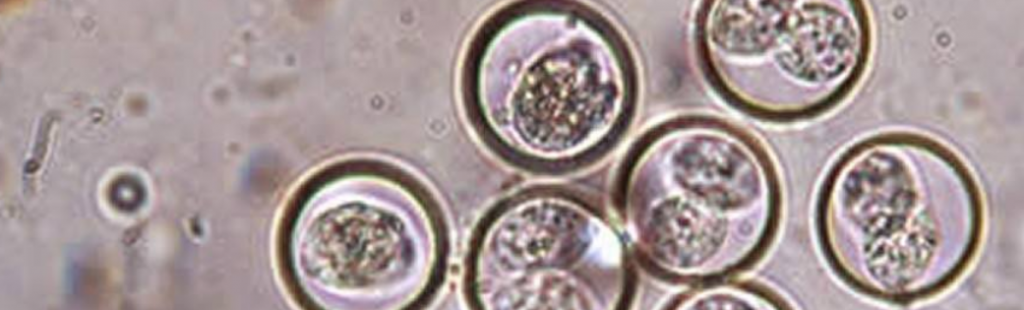

Coccidiosis affects all ages of pigs and is a tacky or watery diarrhoea, piglets do Read more

(When sourcing stock IT IS UP TO YOU to ask the breeder if they have Read more

Gastric ulcers in our pigs can affect all ages, but is more commonly observed in Read more

The Pigs Eyesight The OSBPG Charity is always looking to investigate the wonders of pigs Read more

Studies and investigations conducted by pig geneticists and leading experts in the field emphasise the Read more

It is extensively documented that during the 1960s, as the UK pig industry underwent intensification Read more

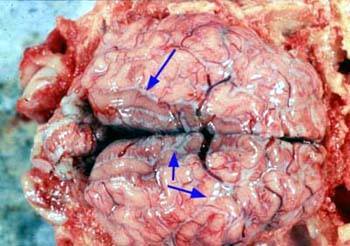

The brain and spinal cord are protected within bony cavities (the skull and the spinal Read more

We all get frustrated when our sow/gilt return and we find that they are not Read more

Here at the Oxford Sandy and Black Pig Group (OSBPG), our supporters all use different Read more

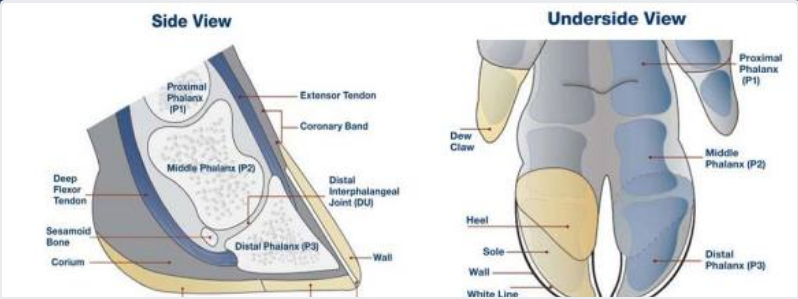

Similar to humans, the feet of pigs bear the weight and undergo considerable strain with Read more

Although not a common ailment with the Oxford Sandy and Black Pig breed, it does Read more

As we witness the wonderful farrowings with the anticipation of more to come, I thought Read more

Enhancing the In-pig Sow Nutrition Although the last month of pregnancy is the period when Read more

Cross- Fostering When dealing with large litters and you have simultaneous farrowings, there may be Read more

Pre-weaning care of the Oxford Sandy and Black piglet Read more

Enhancing Nutrition for Improved Piglet Growth Instead of increasing feed levels, it's worth considering an Read more

Economic Considerations Regarding Low Birth Weight Pigs As we know, and have experienced ourselves as Read more

Swine Flu Similar to humans, pigs are susceptible to colds and flu, especially in the Read more

Porcine Parvovirus (PPV) PPV, while not outwardly noticeable in our pigs during day-to-day observation, poses Read more

PLEASE REMEMBER TO SIGN UP TO THE DISEASE CHARTER WITH AHDB PORK. When sourcing stock Read more